Tendon Reaction Injuries

Those who have already seen me for tendon related injuries will know how much I love to treat them. They are vital for structure and function; however, they are also important for performance in the sporting setting.

The typical tendon injury patient presents to me after months (sometimes more than a year) of ongoing pain that has failed with treatment from other health professionals. To treat tendons, you must be confident in your diagnosis and then understand how tendons function and react when injured. The primary role of tendons is to attach muscle to bone, store and release energy and improve explosive power. Tendon cells are known as tenocytes which are made up of collagen proteins. Collagen is an essential protein involved in providing structural support to cells.

Tendon injuries occur due to a homeostatic imbalance between wear and repair. There are different risk factors that influence this balance, some of these being non-modifiable (as there always is).

Risk Factors that influence the WEAR on the tendon

TRAINING LOAD – This is largely the biggest contributor to why tendon injury occurs

Previous tendon injury

Muscle weakness

Lower limb biomechanics

Footwear

Training surface

Risk Factors that Influence the REPAIR on the tendon

Tendon structure – Negative structure changes are associated with tendon injury

Increased BMI/Adiposity – Increased negative inflammatory markers

Diabetes – Results in negative structural changes to collagen in the tendon

Medications – Corticosteroids/statins, whilst Fluoroquinolones are associated with Achilles tendon rupture!

Increasing Age – Change in mechanical properties and decreased collagen turnover

Genetics

Sedentary behaviour – Disuse of tendon leads to tendon pathology

Sleep/stress

Smoking

Rheumatological Disorders

Training load is a massive risk factor for the occurrence of tendon related injury. Doing too much too soon results in a tendon reacting to the stress. Tendons need appropriate rest in between high load exercise bouts to adapt positively.

Why this is the case and how much rest is appropriate?

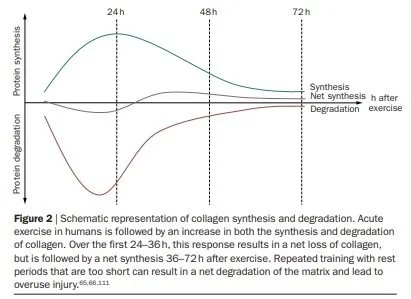

As mentioned earlier, collagen is an essential protein that provides structural integrity to tendons. In a study from (Magnusson et al, 2010) they investigated and found what a high load of exercise does to the collagen in tendon cells up to 72 hours post exercise. Now remembering that tendon health is about finding the right balance between tendon wear and tendon repair. In their study they found that collagen is in a net loss of degradation in the first 24-36 hours post high load exercise. However, they then found that the collagen then goes into a net synthesis of adaptation from hours 36-72 post exercise after high load (represented in diagram).

So after high loads of exercise, it may be important to allow up to 36 hours of adequate rest or very low loaded exercise before completing another subsequent bout of high load exercise. This study certainly is why I program tendon injuries the way I do.

(Magnusson et al, 2010)

Sedentary effects of exercise – It also leads to tendon pathology

As can be seen in the risk factors, being sedentary and having an increased BMI due to adiposity of fat tissue leads to tendon pathology. So too much exercise can result in injury to the tendon and not enough exercise can also result in injury to the tendon. The research by Cook & Purdam (2009) illustrates this continuum of finding the appropriate balance between wear and repair. If doing too much or too little exercise, then you get a reactive tendinopathy. However, if the balance of finding appropriate tissue capacity is found then, happy healthy tendon is the result. This model of overload vs underload is also very relatable to all tissues in the body!

Cook & Purdam, 2009

What happens to the tendon when pathology occurs?

There is a degenerative and inflammatory component. The tendon makes structural changes that are not ideal for optimal function. The collagen becomes disorganised and there are less mature collagen proteins, with larger concentrations of immature collagen bundles. The tendon cells increase in number/metabolic rate and there is an increase in cell death.

The inflammatory component involves mediators that increase pain and water content into the tendon (resulting in a thickened unhealthy tendon). This negative inflammatory process results in an influx of blood vessels and nerve fibres ingrowing into the tendon. This all results in a painful angry tendon!

How does the change in tendon structure influence function/performance?

As mentioned earlier, the function of the tendon is to be an elastic energy storage and release spring. Tendinopathic tendons have less elastic and stiffness properties which therefore affect explosive performance. It can also result in less muscle force being applied and affects the stretch-shortening cycle. Therefore, having a tendinopathy not only results in chronic pain, it also affects speed, power and hopping/jumping in lower limb tendinopathies.

In summary – Plus a few extras

Tendon injuries like most injuries are due to an imbalance between activity and optimal rest periods. They are slow healing and result in negative structural changes when a tendon reaction occurs. However, they can heal and their management involves slowly loading the tendon over time to allow it to adapt. They are likely to occur to sustained higher loads when they are being compressed against a bony landmark in the body. This is important and your health professional needs to understand this so they can tailor rehab to your individualised tendon injury.

I explain tendon rehab as if dating a very picky individual. If you give them too much love, they will get overwhelmed and angry. If you don’t give them enough love, then they will also get angry. If you then hug (compress) that angry person, then they will probably not like it either. With tendons it is on their terms, give them what they want!

References