Pain and Exercise – Is it safe and beneficial?

I am very passionate about this topic for many reasons. The old school thinking of resting completely after injury is quite outdated and very rarely, in my opinion, should be prescribed. There are times where rest is needed post injury, however this must be educated to those injured so they understand the benefits of when to rest and when to load (exercise). As I have mentioned before in previous blogs, most musculoskeletal injuries are a result of the absolute load being applied exceeding the loading capacity of the worked tissue. For example, if an untrained individual started running upwards of three kilometres a day, then they will likely in a few weeks suffer with an overload injury (as their body was not trained to tolerate the repeated loading). Shin splints, Achilles tendinopathy or ITB compression pain are frequent injuries as a result of this type of overload. So, a gradual build up of exercise with appropriate rest is what is needed here. This build-up of load should be slowly progressed over a few weeks until tissue capacity is met with tolerance.

Rest is important! But post injury too much rest can be detrimental to recovery and overall tissue capacity. When we suffer an injury, tissue capacity is affected and therefore we need to rehabilitate back up to appropriate levels of this capacity. If we were to rest completely until pain was gone, then tissue capacity would likely further decrease as a result of not exercising. This would then lead to rehabilitation having to start at a lower tissue tolerance in order to not exceed the capacity of the injured/untrained tissue. This whole process is likely a reason why injury recurrence is so high for many musculoskeletal injuries. So, rehabilitation is a little bit of trial and error as we need to find a suitable load that your body can tolerate and adapt from. The famous physio Phil Glasgow quote, “Rehab is training in the presence of injury”, is important to remember here as when there is an injury present, pain therefore may also be present whilst we are rehabilitating the injury.

Is it safe to train through pain?

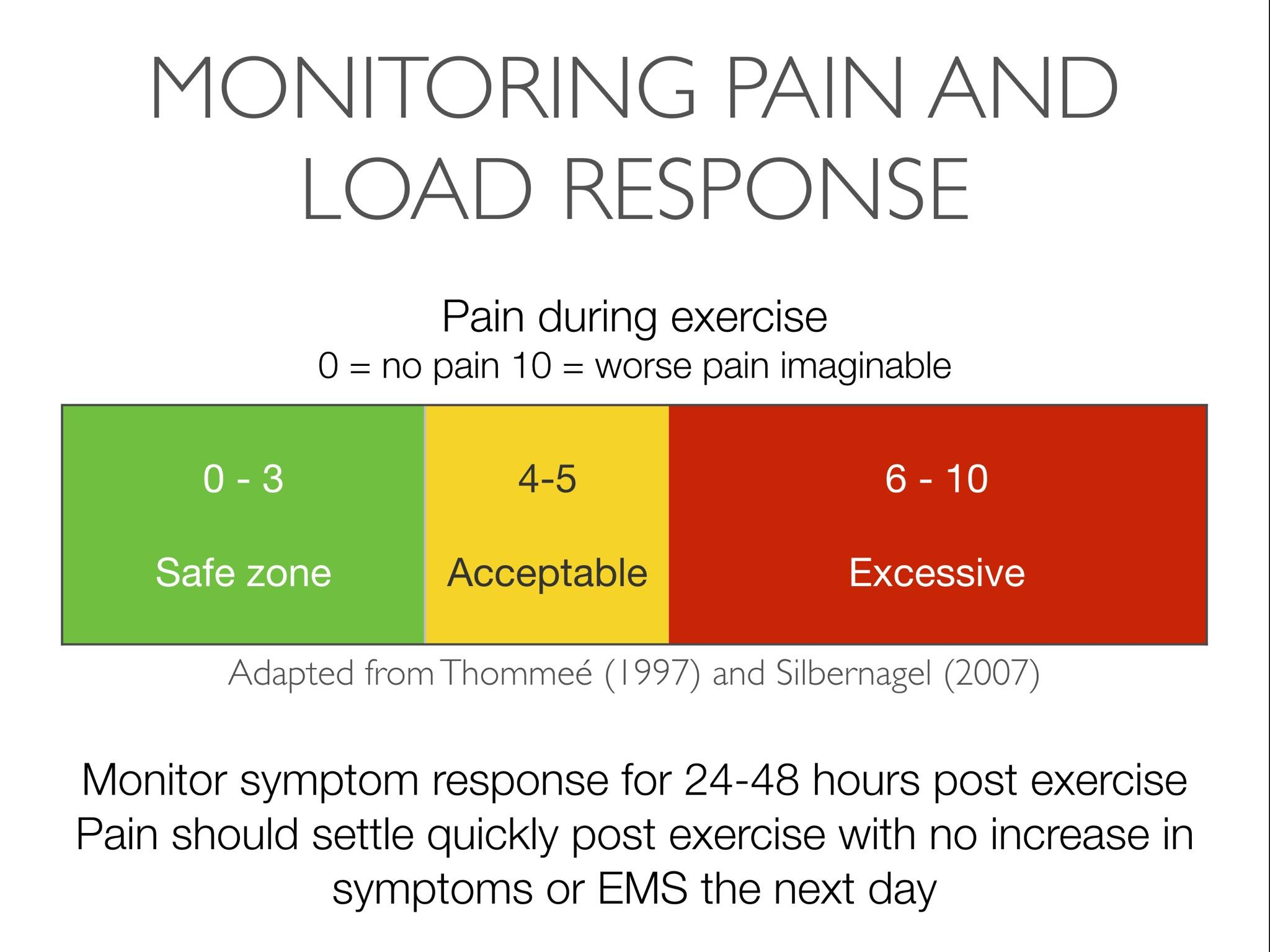

There has been a lot of great research in this area, comparing the benefits vs risks of training with pain to overcome pain. Everyone has their own pain tolerance levels, so this is important. We must respect individual’s own views when describing pain and if the exercise/movement feels good or bad. A lot of the research has used the Pain Monitoring Model which ranks pain from 0-10. Pain from 0-3 is rated ‘safe zone’, 4-5 rated ‘acceptable’ and anything 6-10 is ‘excessive’ and should be modified or stopped.

Pain Monitoring Model: Source Physio Network

Research by Smith et al (2017) in a high quality systematic review and meta-analysis investigated and found that protocols of exercise rehabilitation using a pain monitoring model approach had significant benefits in the short term over those who went a pain free approach. More research is needed to investigate long term outcomes, though. Another research paper (Smith et al, 2019) investigated the proposed mechanism on why painful exercise provided benefits to recovery. The proposed benefits include central and peripheral pain modulating mechanisms where pain inhibits pain. There are also positive immune system responses and psychological aspects (improved confidence and self-efficacy to injury/pain and recovery). There is good research that supports early loading (after injury) through tolerable pain levels in hamstring rehab, where there were no detriments to recovery time and improved strength and function in those in the pain tolerant rehab group compared to those doing pain free exercises (Hickey et al, 2020). So the evidence supports and encourages loading when we are rehabbing an injury/pain as it is safe and may in fact be more beneficial for many different reasons.

What can we do to adjust exercise to make it tolerable?

There are many ways we can change this. I personally have the luxury of using the facilities inside Project Reform to get the best patient outcomes. The first thing we can change is load (reduce weight in exercise). We can change the effort put into the exercise. If pain is high, then reduce the number of reps performed in the exercise. We can alter the range of motion, if the exercise hurts in a specific range of motion, then perform the exercise in a range that is more tolerable. Another modification can be speed at which the exercise is performed. Slowing the exercise down with more control may result in a more tolerable exercise. Typically, when the pain is more irritable, we need more control. Once it is less irritable, then we can be a little more chaotic with speed. You can reduce the frequency and volume of the exercises. By reducing the amount of sets we reduce the frequency and by reducing the number of days we rehabilitate per week, we reduce the volume. Another variable we can change is the rest time between sets or days between exercise bouts. By increasing the rest time, it allows the body to become less irritable and improve the quality at which we perform the exercises. Lastly, we can change the variation at which we perform the exercise. For example, a lunge may be more painful whilst a squat may be more tolerable. They train the same muscle groups; however every exercise can have regressions and progressions.

What if there is pain after the exercises?

This is normal and expected. However as mentioned before, rehabilitation is trial and error. We are trying to find the appropriate tissue tolerance at the current time. THE GENERAL RULE is to monitor pain levels post exercise for the next 1-2 days. Pain should not be worse than it was previously and should subside over the 1-2 day period. If pain is worse, then reduce load. If pain is the same as previous or improved, then continue as prescribed. Always speak to your health professional if you are unsure at any stage.

In summary

Pain with exercise is safe and does not equal harm when exercising at tolerable levels (as described above)

Tolerable painful exercise has multiple benefits for improving pain, function, immune response and self-efficacy/confidence

Exercises can always be modified through various ways to make them more tolerable

Post exercise soreness is also ok, just monitor levels and ensure they are not worse than what you previously felt. This pain should subside over the next couple of days!

If you have had ongoing pain or been battling injury, then we can help at The Reform Lab Osteopathy. We have elite facilities that you have access to as part of treatment inside Project Reform. We want to help you so you can help yourself!

References